Fine Art Photography

JOBO IS BACK!

Good news for those of you that use Jobo products for processing in your wet darkroom. Posted on the Internet below from Firscall Photogaphic LTD, located in Taunton, Somerset, UK.

Jobo Announces first Film and Print Processor in over 20 years!

Posted on April 3, 2012 by Firstcall Photographic

Jobo stopped production of its rotary processors in 2010. In doing so it became the last manufacturer to market a range of film processing machines to photographers.

With the resurgence in demand for film usage, reduced mini-lab sites and film processing in multiple retailers, they have decided to re-tool to make a new film processor that will be available in the last quarter of 2012.

Based on the original design for the Jobo CPP2, the new model has the initial product code of CPP3 and will have the capability to process all types of film and paper. It will have accurate temperature control, timer and take all Jobo tanks up to the 3000 Expert (sheet film tank system). The original CPP2 concept will also be maintained in that it will have both cog and magnet lid connection for use with a lift and normal rotary agitation.

To get a technical Specification and a free £290 lift with purchase of the processor send your name and contact info to info@firstcall-photographic.co.uk

BEER & RODINOL

When I first began working with B&W in my own darkroom I only had a 35mm camera. So I shot many rolls of 36 exposure Tri-X. At one time my favorite developer was Rodinol. Not very expensive, easy to use, keeps forever and I liked the negatives. What else could you ask for?

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.

My procedure for film was simple. I would line up my chemical containers in the correct order. Fill them with the proper liquids and adjust the temperature. Then I would head to my closet darkroom to load the film into the developing tank. I used a 16oz tank that held two reels and I usually did two rolls at a time. I loved the Rodinol because it came in a stock syrup and was mixed something like 1:200, if memory serves me correctly. I would measure the stock using two small syringes since it only took a few milliliters to make up the developer. I would lay the syringes, once loaded, next to the container marked developer which contained distilled water. I always have used presoak, so once the film was in the presoak, I would empty the syringes into the developer container and stir up the developer. Not much to it, simple and easy. Usually took me about forty five minutes from start to hanging up film to dry.

Now this one particular Saturday myself and a few friends went out and I shot two rolls of film that day. Later that evening we returned to my place for a few beers and by about 8:00 everyone headed home. I had this bright idea that if I processed the film from the day it would be dry and I could print it Sunday. Nothing to it, just get out the notebook, measure and slosh. . . processed film!

There was nothing very special about this film run, except the slight fog in my head from the beers and maybe a little to much sun. Everything went as usual. Once the film was washed I unrolled the first strip to find it completely clear end to end. The second roll was the same. What the @#$%^*? My first thought was the camera quit working. As I sat there perplexed I looked at my processing line and what do you think I saw? There next to the empty container for the developer lay my two syringes with the stock Rodinol still in them. I had failed to mix the developer. I learned right there that plain distilled water will not develop film. I also immediately enacted a strict rule in the darkroom; NEVER MIX RODINOL AND BEER!

JB

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.CROPPING

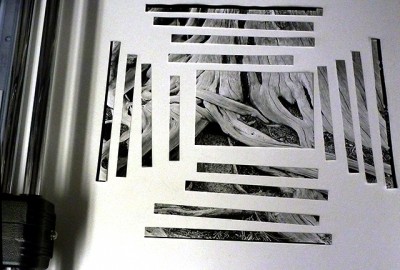

Those that dictate hard and fast, unwavering, rules for the creation of art usually are the vane, egotistical, self-centered types that are full of their own over-inflated view of their importance and try to tell you that cropping is an unforgivable sin. I say. . . Not True!

Those that dictate hard and fast, unwavering, rules for the creation of art usually are the vane, egotistical, self-centered types that are full of their own over-inflated view of their importance and try to tell you that cropping is an unforgivable sin. I say. . . Not True!

No one has the authority, nor the right, to tell you what, nor how, to create your art. Cropping is a personal decision, and can only be justified by you as an individual. If cropping helps any particular photograph, then it is no sin to proceed to crop away.

Cropping is best done in the camera at the time you make the negative, but it is not always possible. There will always be those instances that appropriate framing is just not possible in the field. Never pass up an opportunity just because the perfect image does not exactly fit the film. Keep cropping as an option. Do not dismiss anything that will help.

During the printing process look carefully at your first work print and determine if the image is strong from corner to corner. Use cropping L’s to mask questionable edges of the image and determine if lopping off some of the image will strengthen it. If you are enlarging you can reset the easel and the print size. If you are contact printing, a rotary trimmer is your best friend. The choice is totally yours. Do not be a slave to others opinions. There are no rules. The decision is so eloquently expressed by Bob Segar: “What to leave in, what to leave out. . .”

If cropping does not improve the photograph, maybe it is a good idea to find another image that will be more expressive. If you do hit a brick wall with a photograph, save your work and put it aside for later. There are few negatives of questionable substance that are worth killing yourself in order to print. You are usually better off to concentrate on those that are not a struggle to print.

It is easier on you and more productive, and less frustrating, to make negatives that are well seen and easy to print. A mastery of craft will make everything work more smoothly, but never let anyone tell you that you should not, can not, crop your photograph. Just don’t go there! Cropping can be your best friend.

JB

DON’T LAY IT ON THE GROUND

Strange how many questions we get about what we do, why we do it, and always how do you do certain things. I never mind answering questions. This is how one learns, and I feel that sharing what you know is very important. We have no secrets. . . no secret methods. . . secret places. . . secret formulas. . . or anything that is in any way secret.

Strange how many questions we get about what we do, why we do it, and always how do you do certain things. I never mind answering questions. This is how one learns, and I feel that sharing what you know is very important. We have no secrets. . . no secret methods. . . secret places. . . secret formulas. . . or anything that is in any way secret.

Funny how after our last trip, and sending out our Utah Snapshot Album, I received several questions about our camera packs. One that came up several times was how do you hang the pack from your tripod? We are pretty picky about our camera gear. It is imperative when you are a film photographer to keep any and all foreign materials as far from your gear as possible. I just could never set my backpack down in the dirt, let alone the mud, or snow. HERE is another post on this subject.

We tend to photograph in remote locations. We are always climbing over rocks, and are knee deep in mud or snow. One of the first packs I used was a really well-made and versatile Art Wolfe design that was perfect for a 4×5. The pack had a small webbing loop at the top and I soon found myself hooking it to one of the knobs on my Zone VI tripod. Worked great!

We tend to photograph in remote locations. We are always climbing over rocks, and are knee deep in mud or snow. One of the first packs I used was a really well-made and versatile Art Wolfe design that was perfect for a 4×5. The pack had a small webbing loop at the top and I soon found myself hooking it to one of the knobs on my Zone VI tripod. Worked great!

Things were fine until we moved up to larger cameras and larger packs from f64. They say necessity is the mother of invention. So we modified the larger f64 backpacks with a hanging strap similar to the Art Wolfe design, since it was not a standard option from them. Later when we designed and built our own packs the hanging loop was a standard, must have, feature. As our packs got larger and heavier we eventually changed over to Ries tripods and suddenly there was another problem. . . no good place to hook the pack. This was  a challenge. When I need to think about something, I usually take a nap. I do my best thinking when asleep.

a challenge. When I need to think about something, I usually take a nap. I do my best thinking when asleep.

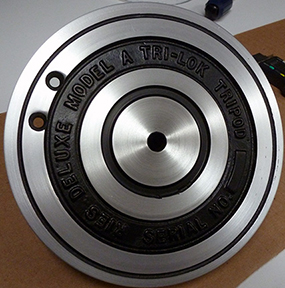

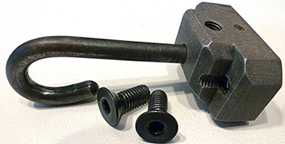

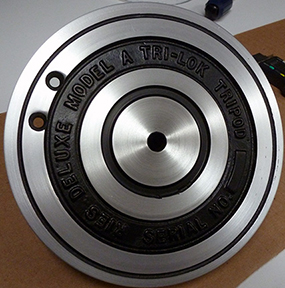

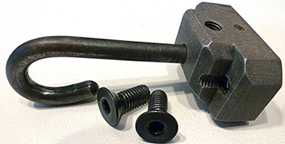

I dreamed up a simple modification to the Ries tripod head that allowed me to add a hook to the under side of the crown. I fabricated a small aluminum block and a hook made of 3/16 steel rod. The rod has to be heated and bent into shape, then quenched to harden the metal. The block uses a 6-32 set screw and a press-fit pin to hold the hook firmly in place. The hook assembly is attached using two 8-32 flat head machine screws drilled through the tripod crown.

I have added this modification to both our ‘J’ and ‘A’ model Ries tripods and they have preformed flawlessly for years. Ries tripods are extremely well-made and will support well beyond their factory weight ratings. I have hung a 45 plus-pound pack from my ‘A’ model for years now and never had any issues. . . except sometimes heaving that heavy pack onto the hook when in a difficult position.

I have added this modification to both our ‘J’ and ‘A’ model Ries tripods and they have preformed flawlessly for years. Ries tripods are extremely well-made and will support well beyond their factory weight ratings. I have hung a 45 plus-pound pack from my ‘A’ model for years now and never had any issues. . . except sometimes heaving that heavy pack onto the hook when in a difficult position.

Take a look at the photos to get a better idea of how I made this modification. I just did a complete rebuild of my 40 year old Ries ‘A’ model and it now has a new coat of paint and the legs have been refinished. It will not stay this nice looking for long. A tripod takes a beating in the field.

The running story around here is that we don’t own much of anything that hasn’t been taken apart and modified in some way. If you work with LF and ULF, you soon learn that there are very few off-the-shelf options available. If you need something, it is probably not made and you will either have to improvise, modify, or build it yourself.

This is how we solved the problem of keeping our pack off the ground. There are those times you just have to make a few modifications.

JB

We tend to photograph in remote locations. We are always climbing over rocks, and are knee deep in mud or snow. One of the first packs I used was a really well-made and versatile Art Wolfe design that was perfect for a 4×5. The pack had a small webbing loop at the top and I soon found myself hooking it to one of the knobs on my Zone VI tripod. Worked great!

We tend to photograph in remote locations. We are always climbing over rocks, and are knee deep in mud or snow. One of the first packs I used was a really well-made and versatile Art Wolfe design that was perfect for a 4×5. The pack had a small webbing loop at the top and I soon found myself hooking it to one of the knobs on my Zone VI tripod. Worked great! a challenge. When I need to think about something, I usually take a nap. I do my best thinking when asleep.

a challenge. When I need to think about something, I usually take a nap. I do my best thinking when asleep.

I have added this modification to both our ‘J’ and ‘A’ model Ries tripods and they have preformed flawlessly for years. Ries tripods are extremely well-made and will support well beyond their factory weight ratings. I have hung a 45 plus-pound pack from my ‘A’ model for years now and never had any issues. . . except sometimes heaving that heavy pack onto the hook when in a difficult position.

I have added this modification to both our ‘J’ and ‘A’ model Ries tripods and they have preformed flawlessly for years. Ries tripods are extremely well-made and will support well beyond their factory weight ratings. I have hung a 45 plus-pound pack from my ‘A’ model for years now and never had any issues. . . except sometimes heaving that heavy pack onto the hook when in a difficult position.REWORKING MY RIES ‘A’ MODEL

It is really great to be able to fix, repair, and restore your equipment yourself. I have always been a doer. . . I like to maintain and work on my own equipment when I can. On our last trip to Utah I noticed that my very old and trusty Ries ‘A’ Model tripod was beginning to show signs of use. I have no idea how old this one is, but I would guess it was manufactured in the late 1970’s or so. I have had it for years and it was no where new when I purchased it. The legs have taken a beating, needed a little work and a refinish. The top crown paint was chipped and peeling and the previous owner had not used a friction washer between the head and the crown, so the crown top was pretty scared up and needed some attention also.

What I had in mind was a complete strip down of every part of the tripod, remove all old paint and finish, repair dings and dents as best as possible, refinish everything, then reassemble. It’s not that hard to dissemble a Ries tripod. Take care not to damage anything and maybe take a few quick snapshots before you start, just in case you don’t remember exactly how it all fits back together.

I completely disassembled the legs, removing all of the hardware so I could sand and refinish the wooden legs. The most difficult things to remove are the drive pins that hold the leg locking rods to the underside of the crown and leg swivel guides. An appropriate size punch makes short work of the pins and an arbor press takes care of the guides.

At this point I have the entire tripod completely disassembled. With the application of a little elbow grease, I completely sanded down all of the wooden leg parts, smoothed over the dings, scrapes, and dents, and shot three coats of spar varnish on all six upper and three lower legs. Next I stripped the old paint from the tripod crown. Took a few tries and some scrubbing with a brush, but soon I had nothing but bare aluminum. Since the crown top surface was scored, I chucked the head in the lathe and resurfaced the top. Next came a fresh coat of black self-etching primer and a bake in the sun for a day. There is nothing like a day or two in the Texas sun to really cure paint. . . even in winter.

The leg swivel guides did not fare well being removed from the crown, so I machined a new set. Once I had the new guides pressed into the crown I also made a new set of friction washers.

At this point it was just a matter of cleaning up a few odd parts and reassembly of the entire tripod. I did not need to do any work on the A250 head since it is much newer than the legs so it was only a matter of adjusting the leg tension and my tripod was ready for action.

That is the entire process in a nutshell. The tripod, though it will never look factory new, is now ready for another trip.

JB

MIXING YOUR OWN

I have always been an advocate of vertical integration. The more you can do yourself, the better control you have of the outcome. For many years I used prepackaged photo chemicals and have never had a problem. But, as the traditional darkroom and the materials used become more and more an alternative process, commercially available photo chemicals are getting harder to find. Some favorite chemicals have vanished. An old favorite, the Zone VI line of print developer, fixer and hypo are now gone from Calumet. I recently witnessed 8 bags of print developer and 2 bags of print and film fixer selling for $127.50 on eBay. That is well over double the original cost from Calumet.

I have always been an advocate of vertical integration. The more you can do yourself, the better control you have of the outcome. For many years I used prepackaged photo chemicals and have never had a problem. But, as the traditional darkroom and the materials used become more and more an alternative process, commercially available photo chemicals are getting harder to find. Some favorite chemicals have vanished. An old favorite, the Zone VI line of print developer, fixer and hypo are now gone from Calumet. I recently witnessed 8 bags of print developer and 2 bags of print and film fixer selling for $127.50 on eBay. That is well over double the original cost from Calumet.

The bottom line is, you can mix your own photo chemicals. Sometimes, if you purchase bulk raw chemicals, you can even save a few dollars. Another plus to mixing your own is the fact that you have 100% control. If something goes wrong, you know who to blame. You can also modify the formula and experiment. Mixing your own photo solutions is not hard. It is not rocket science and you do not have to be a chemist. If you can follow a recipe and bake a cake, you can mix your own chemistry for the B&W darkroom.

The first thing you need to understand is that in order to mix your own photo chemistry you will be handling CHEMICALS. If you are not comfortable with this thought, do not even go there. But, remember that you are surrounded with chemicals. . . the entire planet is made of them. If you take proper precautions and are careful, there is nothing to fear. I am not a chemist, so I have little understanding of deep details and I have even less inclination to study chemistry. Do as I do, assume that everything you handle in the way of raw chemicals are toxic. Do all mixing in a well-ventilated area. Clean up spills immediately. Avoid breathing airborne powders. Always wear gloves and purchase a respirator with proper filter. A little common sense goes a long way.

As I said before, for me, mixing photo chemicals is nothing less than following a recipe.

As I said before, for me, mixing photo chemicals is nothing less than following a recipe.

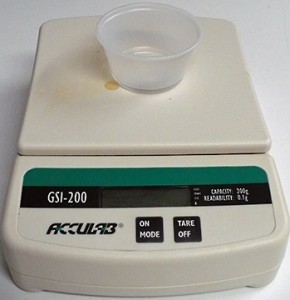

When mixing any photo chemistry formula/recipe you need to accurately measure all of the various chemicals. Most formulas call for dry chemicals measured in grams and liquids in milliliters. I have two scales for dry measure. I have a very accurate digital scale for small quantities and an old-fashion triple beam for larger amounts. I picked up a box of small serving containers at the local big box store to be used as disposable containers for measuring small amounts of dry chemicals. I also have larger 8oz plastic cups for larger amounts. Be sure to use the tare function to zero the scale with the empty container before measuring. Zero the scale with every new container, they do not all weigh the same. Once used, I toss them in the trash. I never reuse one of these plastic containers. This assures there is no chance of unwanted contamination.

For liquids, I use an appropriate size graduate, and for small quantities, a pipette is the easiest way to make accurate measurements. You can use a pipette pump to make loading and measuring easier, or just dip the pipette into the container and hold your thumb over the end. Remember to always thoroughly wash the pipette after use and always use a clean pipette when going from one chemical container to the next. If the pipette is not properly cleaned, you will cross contaminate your chemicals.

Always follow the chemical formula. Most all formulas are mixed in water and there should be a temperature specified to insure the chemicals dissolve. Always mix in the exact order as called for in the formula. Add each ingredient slowly and continually stir until each is completely dissolved before adding the next. This is where a magnetic stirrer comes in handy. Take your time. Do not rush the process. Some chemicals take some time to completely dissolve.

I use distilled water for all stock solutions. I always use distilled water for stock solutions and processing film. Unless your tap water has known problems, it should be fine for mixing printing chemicals.

I use distilled water for all stock solutions. I always use distilled water for stock solutions and processing film. Unless your tap water has known problems, it should be fine for mixing printing chemicals.

Once properly mixed, store each formula in a clean bottle with a plastic cap. Never use metal caps, some chemicals will cause them to rust and contaminate the solution. Brown glass is best for developers and plastic should be fine for most others. Be sure to label each container as to its contents and also include the date mixed. Most all stock chemicals are good for three months, some much longer.

There are many published formulas. Some popular commercial formulas are proprietary, but in many cases there are alternative, similar formulas that are published. By applying a little experimentation, you can tailor your photo mixtures to suit you. Search the Internet for formulas and pick up a copy of “The Darkroom Cookbook” Third Edition by Steve Anchell.

Mixing your own is not that difficult. With a little study, careful handling, forethought and experimentation you can mix your own photo chemistry.

Here is a list of things you will need or may want to have;

• disposable gloves

• respirator

• apron

• a selection of required chemicals

• accurate scales

• disposable plastic cups for weighing chemicals

• several sizes of graduates for liquids

• stirring rod

• magnetic stirrer

• pipette

• pipette pump

• glass storage bottles

• plastic storage bottles

Resources:

Bostic & Sullivan

http://www.bostick-sullivan.com

Artcraft Chemicals Inc.

http://www.artcraftchemicals.com

The Darkroom Cookbook Third Edition by Steve Anchell

http://www.steveanchell.com

Pyrocat HD a semi-compensating, high-definition developer, formulated by Sandy King.

http://www.pyrocat-hd.com

The Book Of Pyro by Gordon Hutchings

JB

THE DAY KODAK DIED. . .

A PLACE TO STAND

Ever found that once you have your camera in just the right position that you can’t quite see the very top of the ground glass. It is important to get up there so you can see if your foreground is in focus. Never fails, you need just a little more to get a good view. Well, we found a neat accessory that just may save the day for you.

Ever found that once you have your camera in just the right position that you can’t quite see the very top of the ground glass. It is important to get up there so you can see if your foreground is in focus. Never fails, you need just a little more to get a good view. Well, we found a neat accessory that just may save the day for you.

We discovered a nifty little folding step stool at Wal-Mart. We hauled a couple of these with us on our last trip and though I never used mine, Susan found it very helpful with several of her photographic efforts. It was especially useful for her and the pano format cameras she uses. She made use of the step several times when she needed a little height working with difficult setups.

Here is more information from the Wal-Mart web site;

Keep everything within reach with the Mainstays 12″ Folding Step Stool. This skid-resistant step stool gives you an extra boost to reach high shelves or cabinets. It folds down to two inches thick for easy storage.

Mainstays 12″ Folding Step Stool:

Easy to carry

Skid-resistant top and feet

Stands 12″ high

Folds to 2″ thick

Weight capacity: 300 lbs

Folded Size: 13.5″ x 12.5″ x 2″

Weight: 2.5 lbs

Wal-Mart No.: 007126355

This 12″ step folds up and is easily tucked away till you need a little boost. This is another accessory that is a life saver when you need it. We ended up purchasing several of these for use around the house also. You never know what you are going to find when you are out poking around in the stores.

JB

Easy to carry

Skid-resistant top and feet

Stands 12″ high

Folds to 2″ thick

Weight capacity: 300 lbs

Folded Size: 13.5″ x 12.5″ x 2″

Weight: 2.5 lbs

Wal-Mart No.: 007126355

CLEANING FILM HOLDERS

Dust is forever the biggest enemy of the large format shooter. Seems that no matter how meticulous you are, that one little speck of dust sneaks in and plants itself right in the middle of some nice smooth area. . . like the sky. It is a never-ending battle and requires continuous attention.

It is obvious that you need to keep your camera clean and it is imperative that you vacuum out all of your film bags and equipment cases. Dust gets everywhere, and it is good practice to vacuum everything before you go out to photograph. But, there is one area we have found to be extremely important for dust control, and that is keeping your film holders clean.

We have found that a thorough cleaning of every holder just prior to loading film keeps the dust problem to a minimum. If the inside of the holder is clean, then the outside is the only place where dust resides. Realize that the most critical time is before and during exposure. If a dust speck gets on your film after exposure, at least it is no longer a threat for making the dreaded pinhole which leads to the black spot on the print. After exposure, the worst a dust speck can do is possibly scratch the film during handling.